I’m not sure about you, but I learn best by seeing how something is done and then doing it myself. In that effort, I’ve put together a table top mock up for wiring recessed lights, along with steps and thoughts for running this lighting setup in a real home environment. Recessed lighting is a very popular home improvement project, and this article will help you better understand the wiring components of this job.

The pictures below shows components of my entire table top “system” of new-work, recessed lights, starting at the circuit breaker on the left, and going all the way back to the last recessed can on the right. Click here or on the image below for the full, undivided image of the table top.

Steps to Wire Recessed Lights

Step 1: Obtain the Appropriate Electrical Permits

While not required for a tabletop demonstration, most jurisdictions will require you to obtain a permit for electrical work that includes a new or extended circuit. In some jurisdictions, only licensed master electricians can obtain these permits. You can usually find where to file for permits via links on your county government’s or state government’s licensing and permits web page.

Step 2: Plan the Circuit

In this mock-up installation, I’m using only two recessed cans that are on a dedicated circuit with a single, 15 amp breaker and a dimmer switch. Here’s some basic facts you should consider when installing recessed lights:

- Most lighting circuits in homes are either 15 or 20 amps. 15 amp circuits are the most common.

- 20 amp circuits require 12 gauge wire; 15 amps circuits allow for less expensive 14 gauge wire. Our example uses 14 gauge wire.

- Circuits may be loaded up to 80% of their nominal capacity, meaning that a 15 amp circuit can have 13 amps of loading, and a 20 amp circuit can have 16 amps of loading.

- Some jurisdictions may also impose a limit on the number of individual fixtures on a circuit.

- Most fixtures are rated by wattage, rather than amperage. A 15 amp, 110 volt circuit may be loaded up to 1430 watts (80% of 15amps = 13amps; 13 amps*110 volts = 1430 watts). This means you could theoretically have fourteen 100 watt recessed lights on a single circuit.

- Switches, especially dimmer switches, may have a lower wattage limit than the overall breaker. 400-600 watt limits are normal for dimmer switches. The switch we show in our example is rated for 600 watts.

Considerations for extending a circuit: You may be able to branch off of an existing circuit so long as you do not exceed the total allowed number of fixtures on the circuit.

Code: Most jurisdictions follow some variation of the National Electric Code. You can get limited free access to the NEC via NFPA’s web site.

Step 3: Select the Right Type of Can for Your Project

Old vs. New Work Cans:

- Old work (remodel) cans – mounted to drywall, installed after the drywall.

- New work (new construction) cans – fastened to joists, installed before drywall. (Our example shows new work cans).

Insulation Contact (IC) vs. No Insulation Contact:

- IC cans – appropriate for attic installations and other installations where insulation will directly contact the can.

- Non-IC cans – appropriate for most first floors and basements, or anywhere insulation will not touch the can. (Our example uses non-IC cans).

Step 4: Physically Install the Cans

[This step is outside of the scope of this article, but this is a very simple step, and all can manufacturers will include instructions for installation.]

Step 5: Wire the Cans

The order in which you wire the cans is unimportant, but you should always wait to connect the circuit to the panel until the rest of the wiring is complete. I’ve decided to start with the end of the circuit and work backwards.

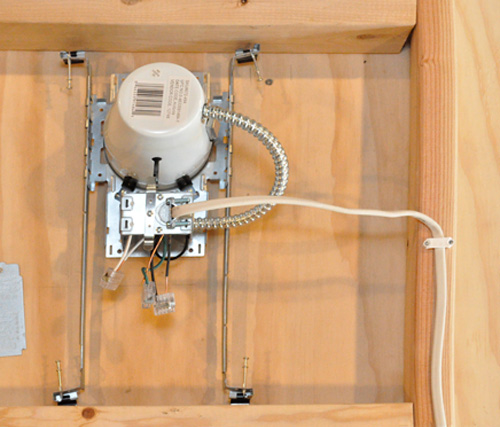

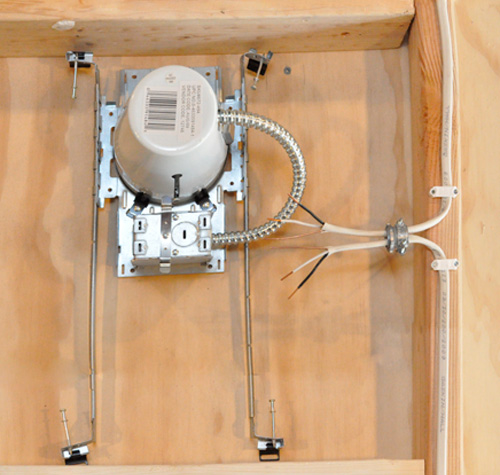

The first picture below shows the last recessed can on our circuit, which is the right-most light on the larger table top picture. I have used 14/2 (14 gauge, 2-wire) NM-B wire to connect the fixture, since I will have a 15amp breaker in the panel. You can see a wire connector in place where the Romex connects to the can to keep the wires tension-free. These wire detensioners are often skipped by do-it-yourselfers. They should not be skipped, because without them, the Romex will rub against the metal hole in the can and can short out, creating a fire hazard.

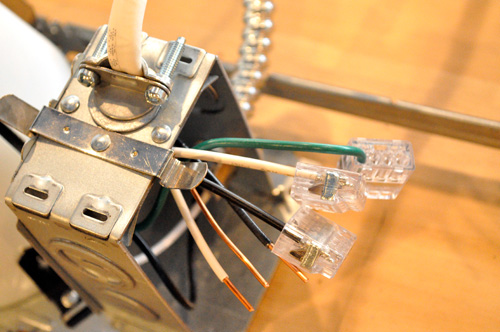

These recessed cans feature push-wire connectors that make it easy to wire everything, even though most electricians prefer wire-nuts (less potential for failure). To wire this light, all you have to do is strip the wires coming into the box back 1/2″ and push the ends into the right slots. The black wires goes together, the white wires go together and the ground wires (bare/green) go together. There are three empty slots per wire type, which means you can have at most a 3-way junction. You can’t see it, but there is a small, metal panel that snaps back onto the box to conceal the wires after it’s all set.

I used 3/4″ plastic cable staples to secure the Romex, and now the wire travels to the next can in the circuit. For this one, I’ve slipped the wire connector (detensioner) on the wires, but I haven’t popped the metal, circular knock-out where the connector attaches to the box. Just like before, all similar wires go into the same push-connector. Even though I haven’t shown it, you can see how this fixture serves as a “bridge” to the last fixture in the group.

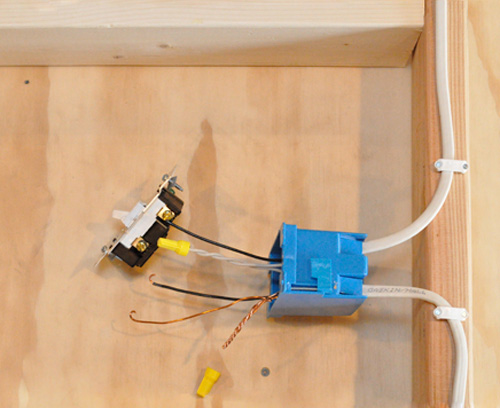

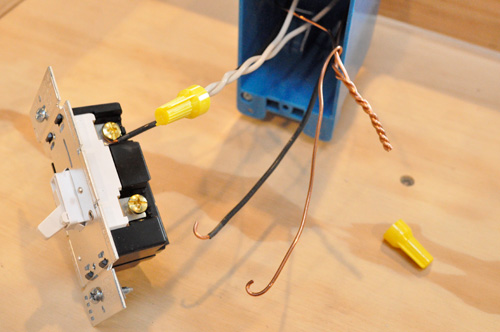

Next up is the light switch, and you can see that I’ve almost completed wiring the switch. Most switches, this one included, have two gold screw connectors. The hot/black wire coming from the power source connects to one gold terminal, while the hot/black wire going to the fixtures connects to the others. Ground wires are twisted together and also connected to the switch. Neutral wires are twisted together and then wire-nutted.

Here’s a closer look, and I want you to notice a few things.

- The wire sheathing is cut just after the wire enters the box.

- All of the white wires are twisted together before screwing on the wire-nut.

- For the ground wires, since they must be tied together and also tied to the switch, a third bare copper is twisted with the two wires in order to go to the switch.

- The black wires and ground wire are curled in the same direction that the screws turn as they tighten down.

- The black wires are stripped only far enough back that the wires will wrap neatly around the screws, but no further.

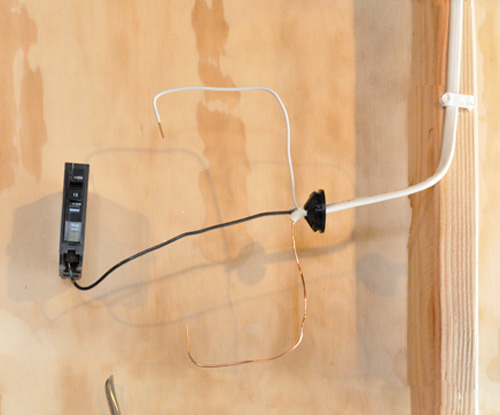

After the switch, the wire goes back to the circuit breaker panel. Imagine that the wire enters the panel at that black connector. The sheathing is cut and the white and ground wires go to the ground strip.

- Note: in the main panel for a house, the neutral (white) and ground (bare) wires both connect to the ground bus. For sub-panels, neutral and ground have separate buses.

The black wire goes to the circuit breaker. There are several types of circuit breakers, and this is a Square D, 15 amp breaker.

Here’s a picture of an actual main circuit breaker panel. With lots of different wires coming in, breaker panels can quickly become very confusing.

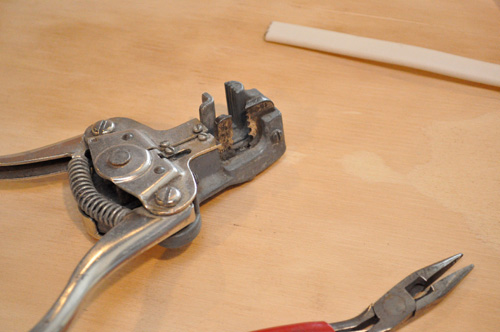

Tools Required for Recessed Lighting

I thought it’d be helpful to know what tools I needed to set all this up. You’ll need the same tools if you’re actually installing recessed lights.

- wire strippers

- needle nose pliers

- utility knife

- screwdriver

- linemen’s pliers

- hammer

I can’t say that I’ve ever seen a master electrician use this style of wire strippers, but I love ’em. They work for different gauge wire, and they push the sheathing right off.

This is how a lot of recessed lights are wired, and I hope you find the pictures helpful.

On the middle lights, would you recommend using a pigtail? Or would you just trust the push-connector on the canister to tie them all together?

No pigtail with connectors or pigtail? If one light goed out will the others stay lit with connectors like a pigtail

I like the tabletop mock up so you can get a clear view of everything. I don’t like the push in wire connectors as they can pull out too easily and don’t exactly make the most secure, conductive connection. Just my opinion though. I like that you mentioned twisting the wires in the switch box before adding the wire nuts. A lot of homeowners/DIYers just think twisting the wire nut on will be good enough.

Can you add some details on brands you’ve used in the past? Have you used any that pre-ship with recessed lights?

Unfortunately, I don’t recall which ones I’ve used..IDeal…Gardner-Bender maybe? really not sure. I did read about a brand called Wagos (which is what a lot of sparkies call all push in connectors) that is supposedly pretty reliable, but never used em myself.

Nice job guys….I too can’t stand the push in connectors. I’ve seen far too many problems with them. Wire nuts work great and they are cheaper 🙂

I’ll write more below, but in this case, these push-type connectors come with the fixtures, which makes them cheaper.

Yet another push connector hater. We cut all of them off our new lighting. We’d rather not spend hours digging through electrical boxes trying to find a lose connection.

for me it’s ” I learn best by seeing how something is done and then doing it myself” then figuring out what I did wrong and improving upon it next time. 😀

Is that an IC can, or a non-IC can? Are there any differences in appearance, or is it all in the housing material?

The can shown in our demo is non-IC. From what I’ve seen, larger 6″ cans may be tough to visually distinguish between IC and non-IC. For smaller cans, the IC-versions usually have larger housings built around them (think almost like bigger square boxes) that make them obviously IC. The smaller can shown here is definitely non-IC.

I feel obligated to add a bit more information on push-type connectors for folks who read this thread in the future. The big issues with push-type connectors come from how they hold the wire. Most use a spring-type mechanism, and on some types of these connectors the wires are easy to pull out.

When these push-type connectors first came out, I’m led to believe there were a lot of failures, especially due to loose connections. The push-type connectors on these particular cans are anything but loose. In fact, I’d basically have to destroy the wires to pull them out of the connector. The second concern is around surface area contact and longevity under high load, especially due to heat/cooling expansion and contraction that could create looseness over time. I can’t speak definitely on this. A few observations though:

1) Push-type connectors are deployed on every recessed light I’ve seen, having brought many versions from both Home Depot and Lowes, my guess is that the majority of installers are not cutting them off prior to installation. That’s not to say it wouldn’t be “better” not to, but there’s a lot of residential and commercial installations that have these connectors employed.

2) The connectors are in fact UL listed, and some other sites online note that the good versions of these connectors run cooler than wire nuts under heavy load. I’m not 100% sure why that’s the case and cannot validate the claim, but I think it’s interesting.

It’s hard to argue with the notion that wire nuts are better. For sure, a pre-twisted, properly-applied wire nut is a 100+ year solution. Will these connectors live up to that type of reputation? Hard to say. What you gain by using these connectors is quick installations. Every person will need to make their own decision. If you want to be 100% safe, I say use wire nuts, but I wouldn’t write off a technology just because its first few iterations (or because some manufacturers’ versions) are sub par.

My guess is that some of the push-back on these wires is reputationally-driven, and may not come down to reliable hard facts on current versions of the connectors. I found these discussions also interesting:

http://ths.gardenweb.com/forums/load/wiring/msg0221114516063.html

http://www.contractortalk.com/f5/push-wire-connectors-wire-nuts-39173/

http://www.diychatroom.com/f18/opinions-ideal-push-wire-connectors-42921/

THATS A REALLY GREAT CLARIFICATION OF FACTS VERSUS OPINION VERSUS PERSONAL PREFERENCES.

Any other products where these push style connectors are employed or is it just can lights? I’ve never seen them before other than cans.

Jeff, I haven’t seen these elsewhere in my DIY escapades, just all over recessed lights. You can buy the connectors at local electrical supply shops and home improvement stores, so I suppose they could be used anywhere. They are much easier to use, so it’s a shame that they probably aren’t as reliable as wire nuts.

How many sets of 12 gauge wire can you connect to one non-IC can? I would like to connect 3 sets – one set in from switch, two sets out to two other cans in daisy chain. Then repeat that a three more times. Eight can lights total.

Does it matter where the switch goes in the circuit? Example..First in line from the panel or at the end of the circuit

The switch should go first in line unless you were to wire it old school and have power at the light fixture and use white wire as power down to switch and black as returned switch power.

But this old method is not allowed anymore as Code says all switch junction boxes must have neutral wire present. Keep the switch at the beginning for simplicity

I have a question about my recessed shower lights. They have a black, white, green, and ground wire. Do I connect the green to the incoming ground and the ground going to the can? Thank you

Yes all green wires and bare wires are ‘ground’ and should get connected together

I like everything about this tutorial. Very easy to understand.

EXCEPT the stapling. please don’t staple your wire on top of the rafters in the attic. It’s asking for trouble when someone else goes in the attic and steps on the wire and damages it.

Please staple wire on the rafter side or drill holes and push wire through

Yeah – in an actual attic you would want to be on the side of the joists or trusses. Good tip.

You say what wire is used? is it a what a 14-2 or a 12-2 or a what wire.

Im new to electrical. May i ask if this is a parallel or serial circuit? If one light went out. What would happen to others?

Simply want to say thank you!

If you are installing can lights above the shower/bath are you required to use wet rated wiring for those fixtures since I have wet rated cans and trims? Thanks for such a great illustration!

Just a quick note that you are wrong about 80% of 15. 0.8×15=12, not 13.

So if I’m understanding this right

I can wire four lights in series one to another. I already have a fixture in the area I’m put the cans in to replace. So I can use the power from that fixture to power the cans right ?