Several years ago we wrote a whole series on installing spray foam insulation in our basement. As part of the research for that project, we compared a variety of basement insulation options, including closed cell spray foam, rigid foam board insulation, cellulose, and the staple of most homes — fiberglass batts.

Several years ago we wrote a whole series on installing spray foam insulation in our basement. As part of the research for that project, we compared a variety of basement insulation options, including closed cell spray foam, rigid foam board insulation, cellulose, and the staple of most homes — fiberglass batts.

Insulation options are generally compared by “R-value”, which is a measure of heat transfer. R-value is always proportional to the thickness of the insulation, usually as described in inches. For example, most closed cell spray foams provide between R6-R7 per inch. Traditional fiberglass offers R3.5-R4 per inch (and hence, why the traditional 3.5 inch batts installed in walls are R13).

The problem with R-value is that it measures heat transfer in a perfect installation. This perfect scenario would provide no way for air (or heat) to move around the insulation to penetrate the conditioned space.

Obviously, the problem with measuring heat transfer in a perfect installation is that it ignores the reality that heat can move around the insulation in an imperfect installation. This can create a huge difference in performance, especially for a material like fiberglass which is extremely porous and therefore difficult to completely air seal. If a fairly heavy draft is coming through an exterior wall, it is likely it will find a way to get around fiberglass.

Closed cell foam, on the other hand, completely shuts off air transfer, which eliminates drafts moving through the insulation. For heat to move around in closed cell foam, it literally has to move from one sealed “cell” to the next – an extremely inefficient process. And when it comes to insulation, you want heat transfer to be as inefficient as possible.

Our experience with closed cell foam is that it insulates so well, you would have to install 1.5x – 2x the amount of fiberglass to achieve the same “real” insulating properties as the foam. In other words, R13 of closed cell foam performs similarly to R20-26 of fiberglass. This isn’t going to be universally true, especially if the fiberglass is installed properly.

However, it’s not completely fallacious either. Take the example of insulating a rim joist. In this situation, you have many difficult angles that must be completely sealed from air penetration. Air flow is a particularly acute problem in the rim joist, especially for a first floor, because the joist is often sitting on top of a sill plate which is on top of (imperfect) masonry work. The air penetration at this point can be a substantial factor in heat loss.

The same situation applies in an attic when comparing rolled-out fiberglass batts to additional blow-in insulation. Blow-in insulation is better at covering the floor, which eliminates spots that foster convection. If you want an even better performance improvement, closed cell foam in an attic prevents heat radiating from the ceiling of the house from creating air flows in the insulation, a problem that exists with fiberglass or cellulose installations.

As you can see, R-values can be very deceiving, so it is worth investigating further and asking your insulation installer a lot of questions about how radiant and convective heat transfer will be minimized in the installation.

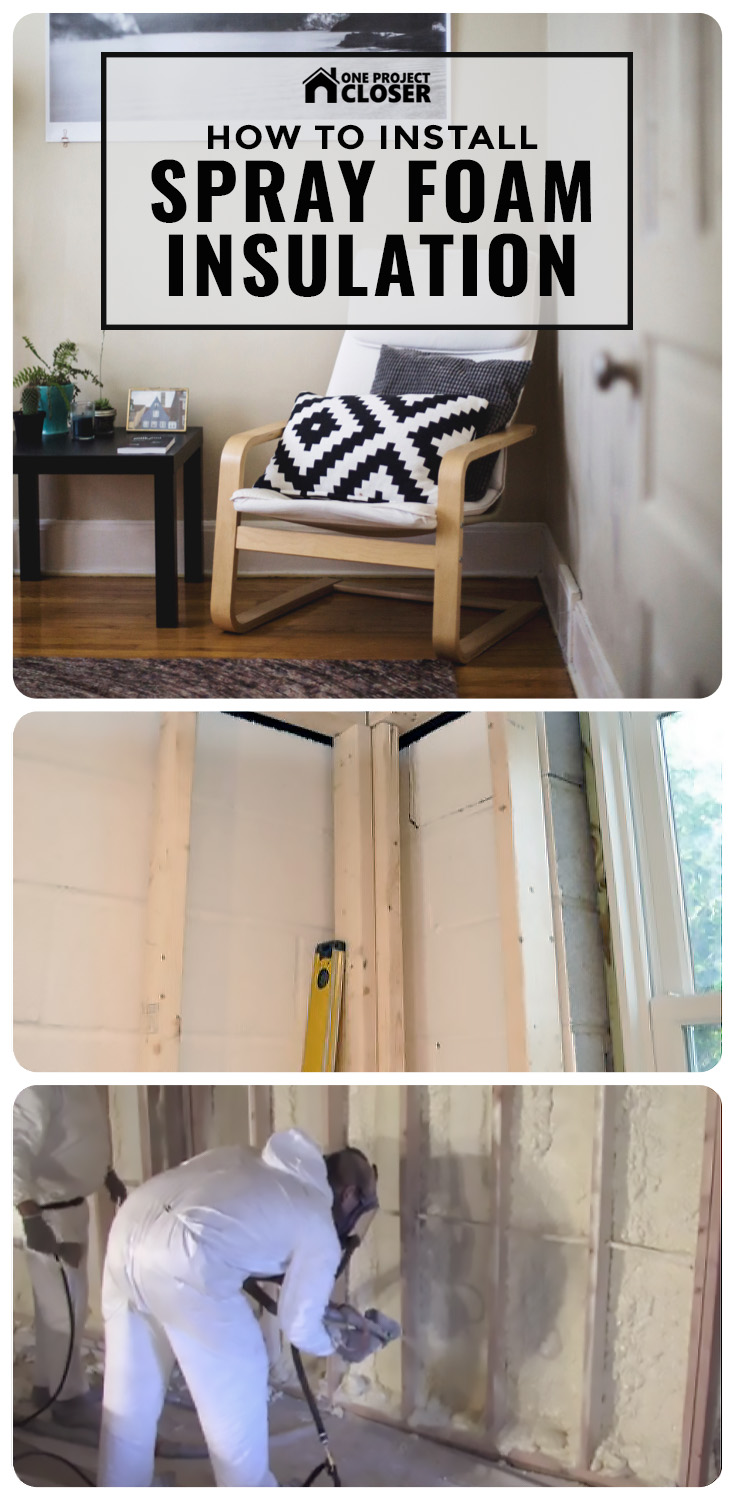

Editors Note: We produced this video on How to Install Spray Foam Insulation a few years ago, and although we didn’t realize it at the time, this spray foam installation represents our very first Pro-Follow. If you enjoy seeing and learning from professional contractors, become an email or RSS subscriber and never miss a Pro-Follow update.

We love sharing unique experiences with our readers, and I’m excited to bring you today’s article! Fred and I had the pleasure of filming Hottle Energy Solutions as they insulated Fred’s basement with spray foam. We worked hard to put out a really comprehensive, high-quality video that will address many different aspects of spray foam installation. If you enjoy the video, please consider linking to this article to spread the word.

There are several different options for insulating your basement and ultimately Fred & Kim chose spray foam. Spray foam is a great choice because it expands to fill tough-to-access space creating a more complete seal than fiberglass insulation. Closed cell foam also has very high R-values, acts as a moisture/vapor barrier and is mold resistant.

This video (9:50) contains a lot of information. We were able to interview the contractor, learn about his equipment, discuss safety concerns, and address some popular spray foam questions. Here are some of the highlights:

- When to have spray foam installed (0:57)

- The difference between open and closed cell foam (1:58)

- The equipment a contractor uses to install the foam (2:35)

- Preparing for spray foam (3:43)

- Pros / Cons of do-it-yourself kits (4:15)

- Necessary safety gear (5:34)

- Health concerns with spray foam (6:13 & 8:27)

- Open cell foam installation (6:32)

- Closed cell foam installation (7:40)

- Final verdict (8:51)

Installing Spray Foam Insulation

I think there are a couple of key points to emphasize from the video.

Frame Off the Wall

Fred mentioned that the framing members were set about 4″ off the basement wall. This is important because that allows our installer to spray foam behind the 2 x 4’s ensuring a continuous barrier all throughout the basement.

Safety Equipment

It’s very important to have the right safety equipment if you purchase DIY spray foam kits. Our contractor had a Tyvek, disposable suit and hand and foot coverings. Make sure to purchase a respirator that includes organic and acid vapor cartridges.

Open Cell Foam

Open cell foam, a.k.a. low density foam, expands to over 100 times it’s liquid size. It’s called open cell because little pockets of air form providing the insulation value. It does not act as a moisture barrier which is an important consideration for basement walls below grade. It features an R-value of about 3.5 per inch. You’ll notice we insulated the band board / rim joist with open cell. Read that link for details about it.

Closed Cell Foam

Closed cell foam, a.k.a. medium density foam, expand to about 25 time its liquid size. Closed cell has such an advantage because it forms a complete envelope sealing out moisture, preventing mold and providing an R-value of 7.5 per inch!

What do you think? What’s your experience with spray foam? Did you like the video?

I was reading an article by Katy over at Charles and Hudson about the benefits of what’s known as a “Cool Roof”. If you recall from our garage spray foam installation, Fred and I opted for a “Hot Roof” on our new, in-progress workshop. Katy’s article got me thinking about the benefits of both Cool Roofs and Hot Roofs over Traditional Roofs, and which option is actually the better choice.

Why We Should Care About Roof Insulation: First up, “Traditional” Roofs

Traditional Roofs (employing asphalt shingles, vented attics, and insulation on the floor of the attic) can get extremely hot, with surface roofing temperatures reaching up to 190° F during the summer. This can easily create attic temperatures as high as 125° F. The hotter an attic is, the more expensive it is to cool the upstairs of a home.

The excessive heat collected by buildings using Traditional Roofs contributes to the Heat Island Effect, a phenomenon where heavily-developed areas (like cities) can be up to 22° F hotter than nearby rural areas. The effect on summertime peak energy demand, air conditioning costs, air pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions is huge.

So what can we do about it? Well, “Cool Roofs” and “Hot Roofs” present two options for tackling the heat problems inherent in a Traditional Roof.

What’s so Cool About a Cool Roof?

Cool Roofs keep radiant heat and solar heat out of your home using a reflective coating on the surface of the roof. Cool Roofs are broken into two categories: low slope and steep slope. Each requires different materials for construction. Each Cool Roof application has different reflectance properties (yes, that’s a real word), so you’ll need to read up before making a selection. Here’s a great guide to learn more about Cool Roofs.

By reflecting radiant and solar heat, a Cool Roof stays up to 60°F cooler than conventional roofs during peak summer weather. The Cool Roof Rating Council claims the “average energy savings range from 7%-15% of total cooling costs.” The EPA references a publication by S. Konopacki, et. al. stating that Cool Roofs provide an average yearly net savings of almost 50¢ per square foot in California. That includes the costs for Cool Roofing products and the increased heating costs in the winter due to lack of solar heat penetration, which is desirable in the winter.

What’s so Hot About Hot Roofs?

Fred an I chose a Hot Roof application (video and review) to insulate the new workshop, meaning the attic is completely sealed and unvented. Air does not flow in or out, and the attic is included in the conditioned space. We achieved this by having 3″ closed-cell spray foam installed directly to the roof sheathing. The term Hot Roof is a bit misleading, as the shingles only get a few degrees hotter than a regularly vented roof.

Think about the electric, plumbing and HVAC that runs through many attics. With a Hot Roof, you’re not digging through insulation to find wires and junction boxes, pipes won’t freeze and burst, and the air flowing through ductwork will stay the right temperature. Additionally, conditioned attics are great for storing stuff, and there’s no concern about extreme temperatures. Hot Roofs act as a thermal break and will prevent ice dams from forming on the roof during winter months.

A Little Q&A on the Subject

I tapped Sean from Alabama Green Building Solutions to help clear up a few lingering questions I had about Hot Roofs and Cool Roofs. Sean is a great resource and I suggest checking out his article about Hot Roofs on SLS Construction.

Would you rather have a hot roof or a cool roof?

Hot roof with a “cool” coating on top. If I had to only chose one – the hot roof hands down. [Apparently, getting *both* is the best option]

Which results in better energy efficiency?

Depends on the location, shade, and a whole host of other items, but you can’t just have the coating without the insulation & proper air-sealing work being done to truly compare them. If you try saying the coating only is enough, you are in for a world of hurt. I would tip the hot roof generally as being the most efficient.

Are different climates better for one or the other?

The hotter the climate, the better a cool roof will help out a properly insulated attic. A hot roof will work “great” in any climate.

Which is more expensive?

Depends on what you are factoring in – all the insulation, the coating, a roof replacement if needed, air sealing, new or existing… The Hot Roof will usually run more, but it generally doesn’t need any ongoing maintenance. Don’t forget that the foam may also need an ignition barrier, which is added cost.

Images courtesy of schuey and NNSANews.

Reader Question: My wife and I are going to be building a new home this spring and have been told that insulating our basement with closed cell spray foam and our exterior framed walls with open-cell foam was the way to go. Is this true or the best way and if so why? Is it because the basement needs a good vapor barrier and the framed walls need some air movement to allow things to dry so mold and mildew don’t form. Also what would be the way to insulate the attic. We live in central Iowa so we get some pretty cold winters as well as some hot and humid summers. Any advice would be greatly appreciated. — Ben

Ben, thanks for the question. This is a complex subject and many builders disagree on the exact right approach. For some reasons why this question is so complicated, I recommend reading this article over at Building Science on vapor barriers and insulation and this article over at Green Building Advisors on open and closed cell foam. Remember, before acting on any advice, read our disclaimer.

Basement Insulation

The builder is recommending closed cell foam for the basement for a few reasons. First, as you said, closed cell foam acts as a vapor barrier, which is important in basement installations. In the summer, humid indoor air can travel through the interior wall and come into contact with the cold exterior basement wall, condense into liquid, get trapped in the wall, and ultimately foster a mold problem. A vapor barrier prevents this from happening. It also prevents other water exchanges between the indoors and outdoors (as described in that Building Science article). Most close cell foams form a vapor barrier at between 1.5 and 2.5 inches of application.

Second, since the basement is below grade, if there ever were a water leak on the inside of the house (e.g. burst pipe), closed cell foam will not absorb water, and thus is much more mold-resistant. Open cell foam will act like a sponge, which will absorb water and actually promote mold growth. Note that if there is a water leak from the outside of the house coming in through the block (e.g. because you didn’t keep your rain gutters cleaned and the water floods right in front of the house), closed cell foam could mask a water problem on the block wall that might otherwise become obvious more quickly. However, I think the risk of this is low, and in all likelihood, if you have that kind of water problem you are going to be in trouble with whatever insulation you install. In this situation, spray foams (both open and closed) are just harder to deal with because they are sprayed in place and are difficult to remove.

Besides dealing with the walls, you may want to consider insulating the floor in the long run. Todd’s article on basement insulation gives some coverage on this topic.

Insulation for the First and Second Floors

The builder is likely recommending open cell foam for the upstairs because a water problem is much less likely on above-grade floors and open cell foam is cheaper to install (although it insulates at about 1/2 the R-value of open cell, per inch). I doubt that the concern is over drying as the builder is likely going to install a vapor barrier just behind the exterior siding or brick work anyway – potentially rigid foam board or polyethylene plastic. The article I cite above at Green Building Advisors has some thoughts on using open vs. closed cell foam that are worth a read on this; they also have some forums there where you can ask questions.

I have heard of more and more homes being insulated completely in closed cell foam because it provides a superior bi-directional vapor barrier and actually adds structural rigidity to the house without the danger of the insulation itself promoting mold, but it remains to be seen whether such approaches would ultimately result in other moisture problems that might actually lead to mold promotion. The exterior materials used to cover the house may have an impact on this decision – especially if those materials are water absorbers, like brick. You definitely want to make sure that if you have a brick exterior (even just a single wall facade) that appropriate plans are in place to keep water off of the interior walls and to ensure that water vapor isn’t trapped between the interior walls and the exterior facade in such a way that drying becomes a problem.

Insulation for the Attic

In terms of what insulation to put in an attic, there are a few competing theories. Some say to insulate the peak of the attic with closed cell foam and seal up all vents to make the attic more comfortable (and actually add strength to the roof). Others say to insulate the floor of the attic with closed cell foam and leave soffit and ridge vents to allow the attic to breath. Still others say to insulate the peak of the attic with open cell foam so that if there is a leak in the roof, the water can escape from the wood and won’t create wood rot in the beams and plywood. As you can see, there are a lot of opinions.

The Right Next Steps

My recommendation is to ask the builder questions about why they are recommending the products and methods they are.

If it were my home, I’d tend towards closed cell foam for the whole house. Why? Because closed cell foam offers 100% air sealing, has higher R-value per inch, and increases the structural rigidity of the house. Sure, you’ll pay more. But if you live in the house for 10 years, you’ll probably make up the cost in energy savings. The only drawback I would be concerned about is the breathing issue – and I would consult a pro to determine if the exterior materials would prevent the use of closed cell throughout.

We installed closed cell foam in our basement last year, and installed open cell in the rim joists. You can see the spray foam video we created during that project. If I could do-it-over, we would have installed closed cell everywhere.

Good luck with your house!

(Image Credit: Giles Douglas)

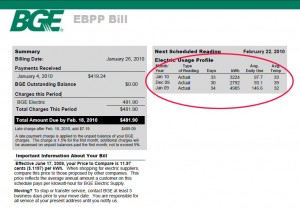

We just received our energy bill for December and January; this is the first bill that shows the full effect of installing spray foam insulation in our basement.

Recall that last year our basement was entirely uninsulated. The only thing between us and the elements were cinder blocks with basement waterproof sealer applied to them.

Our first floor flooring was freezing, and the entire house was drafty. Ultimately, we selected closed cell spray foam from a variety of basement wall insulation options.

We had a local spray foam contractor install the insulation and our subjective experience since then has been great. (In fact, the basement is now the warmest room in our house). Until now, we didn’t have any objective proof that the investment was worth it.

Now we do.

This energy bill confirms our subjective experience with facts. Take a look (click the picture to enlarge and make the numbers legible)…

Energy Savings Analysis

Last January (2009), you can see that our average energy use for the house was a whopping 146.6 KWh / day! This January (2010), our energy use drops to an average of 97.7 KWh / day. This represents about a 33% energy savings, despite the fact that this year’s daily temperature average was 1 degree colder.

Our house is in approximately the same shape as last year, with the same number of people living in it. There are a few differences in the house:

- Last year, we had a large aquarium that we also heated throughout the Winter. While the heat from that aquarium ultimately leaked back into the room, there would still be some increased cost. Our estimate is that the aquarium used approximately $25 / month in energy.

- This year, we’ve been using the fireplace almost every night. Fireplaces are notoriously energy inefficient. They steal heat from a house at a rate much higher than they add back with radiant heat. We still like to look at the fire, though, and we’re willing to pay for for the privilege. I estimate we’ve been losing about $10-$20 / month in energy to the fireplace.

Other than these two differences, the house is in approximately the same shape as last year, with the same number of inhabitants. In other words, we think the bulk of the 33% savings is directly attributable to the spray foam insulation.

Tax Savings for Spray Foam Insulation

The best part: 30% of the cost of the insulation material will be refunded to us this year through the U.S. Government’s tax credits for energy program.

This makes our payback period for the insulation less than 3 years, and potentially even less than 24 months, depending on how the foam performs in the Winter.

Last month we selected closed cell spray foam for the basement finishing project we’re working. Closed cell spray foam has the advantage of not requiring a vapor moisture barrier, and it also sports a very high R value, making it an ideal choice for insulating basements (and first and second floors alike).

Last month we selected closed cell spray foam for the basement finishing project we’re working. Closed cell spray foam has the advantage of not requiring a vapor moisture barrier, and it also sports a very high R value, making it an ideal choice for insulating basements (and first and second floors alike).

A frequent question many homeowners ask is how much R value do different spray foams provide? We think that’s an excellent question, and the answer is, like R-values for rigid foam boards, it depends.

Open Cell Foam Insulation Values – R3 – R4

Open cell spray foams are between .5 and 1 lbs per cubic foot, and have an R value of 3.0 – 4.0 per inch of insulation. R values are additive, so you can multiple the number of inches of insulation thickness times the R value to arrive at a total insulation value.

A typical 2×4 stud filled with open cell spray foam will have an R value between 10.5 and 14. This R value is similar to that of R13 fiberglass batting; however, fiberglass generally does not provide as tight a seal as a foam product would, since it is unable to achieve as tight of a seal.

Open cell foam is relatively easy to cut, which allows installers to fill the cavity passed the edge of the studs and to cut off the excess. This can’t be done with closed cell foams, but they require much less thickness to provide the same R value.

Common Applications: Open cell foam is generally used above grade in walls and sometimes in attics. Some open cell foams have restrictions on the spray height (limited to 5-6″ maximum in a horizontal installation).

Price: More than R13 fiberglass; less than closed cell foam. Expect to pay about $1.25 for the first board foot in a room, and $0.80 for each additional board foot, depending on installation size.

Closed Cell Foam – R6 – R8

Closed cell spray foams are between 2 and 4 lbs. per cubic foot. They sport an R value of 6.0-8.0 per inch of insulation, about double their open cell foam counterparts. Just like for open cell foam, R-values are additive.

Two inches of closed cell foam will provide R12 – R14 of insulation. Three inches will get you over R20, more than sufficient for exterior walls even the coldest climates in the United States.

Common Applications: Closed Cell Foam can be used throughout an entire house. It has the advantage of forming its own vapor barrier, and it can be sprayed to any thickness. The only drawback of closed cell foam is the price.

Price: More than open cell foam; one of the most expensive insulation options. But, doesn’t require a separate vapor barrier. Expect to pay $1.75 for the first board foot in a room and $1.25 for each additional board foot.

Check with a Spray Foam Installer – R Values Vary

Before you commit to a spray foam installation, check with your installer to confirm the R value of the product. Since R values can vary from manufacturer to manufacturer, and based on the chemical make-up of the foam, it’s important to understand the specific foam you’ll be installing.

What do you think? Will you install foam in your house?